So my family are amazing. I live with my sister, Hannah Kilpatrick, who is currently a PhD candidate for the Centre for the History of Emotions. The night after seeing my play, Yours the Face, we sat down in a cafe to explore the themes and interpretations from the perspective of her wonderful brain. I am trying to create some kind of a document after each of my shows that discusses the work and the dialogue around it in a creative way. This is mostly to challenge myself. It is incredibly difficult to be both an artist and an arts commentator and commentating on your own art is the most difficult thing. So, of course, I like to give it a shot. Warning: This post includes a discussion of rape and sexual violence within the context of my script and throughout the Middle Ages.

FLEUR: Where are we?

HANNAH: We are in Journeyman. We are having coffee because we just did lots of upside down yoga.

FLEUR: So I guess I’m trying to create some kind of document about my own work each time. Last year it was Cameron but this time I thought it might be really interesting to talk to you because your angle is so different. Do you want to explain what you do?

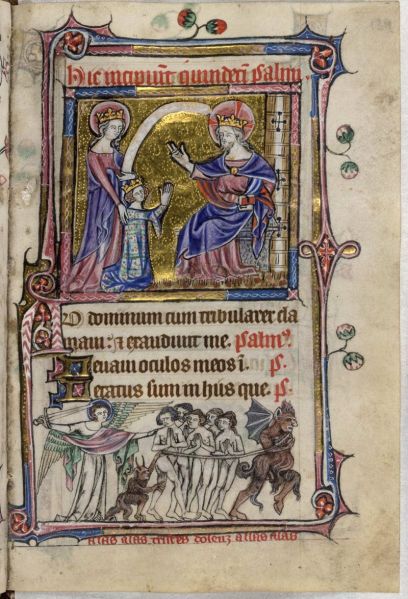

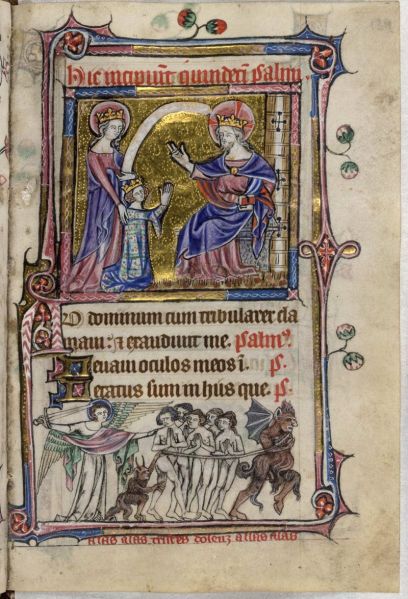

Detail of the devil dragging souls to hell, TAYMOUTH HOURS, England (London?), 2nd quarter of the 14th century

HANNAH: I spend lots of time in front of a computer staring at a screen, which has Latin or Anglo-Norman or Middle English manuscripts on it.

FLEUR: What is your time period?

HANNAH: Mostly 14th Century but contextualising it for a couple of centuries before that.

FLEUR: I’m very flexible with my language. I believe that language is there to be evolved and used and rolled around in. Working in your time period, you see that perhaps more than most people because you see language evolve before your eyes. You’re academic work is at a time before English was standardised and then it was standardised for quite a long time and now it is very rapidly becoming difficult to keep standardised again. Who you say that’s true? I think in this last fifteen years, we’ve had more rapid linguistic changes than in the last…

HANNAH: No, I wouldn’t really say that. I’d say that what’s happened is that for several hundred years we’ve only seen one form of English: the standard central written English. There were of course all the other languages, which were spoken and also written in more marginal ways. In many ways the 20th Century did iron out a lot of regional variations, partly because of the spread of literacy but also because of the spread of things like television and radio, which enforced things like Received Pronunciation on the BBC. There was also the death – or relative death – of so many Italian dialects with wars and migration and being in regiments with people who aren’t from their town or region: it gets flattened out into one broad, general language.

Even before that, rise of the printing press ironed out those variations by making it possible to have one central controlled language. In English, in particular, most English printing presses were in London so it is London English that is going to win out. In one sense, the printing press flattens out the language but on the other hand it opens it out to more people in terms of literacy and availability.

The internet is doing something very similar now in terms of access and bringing different people from across the world together to form tiny little linguistic communities, that have nothing necessarily to do with the language they were brought up with. You develop your own slang, your own ways of shaping sentences, your own forms of punctuation. They’re all written based! They are not about pronunciation! Nobody really knows, for example, how ‘meme’ is pronounced, or ‘gif’.

Our food is brought out to us.

WAITER: Mushrooms?

HANNAH: That’s me, thank you!

WAITER: Aaaaand chilli scrambled eggs.

FLEUR: Thank you!

HANNAH: So at the same time you’ve got the flattening out and the opening up of language. And of course we know how that worked out with the printing press but we’ve yet to see how that’s going to happen with the Internet. I think right now, we’re still at the stage of opening up and seeing what possibilities are out there.

FLEUR: Yeah. Let’s pause for a moment while we eat our breakfast.

The recorder goes off.

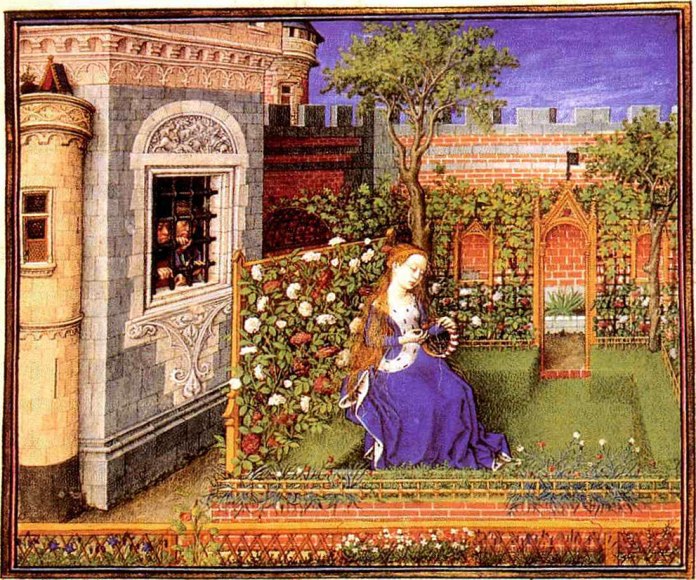

THE KINGHT’S TAKE from Chaucer’s CANTERBURY TALES, 15th Century Manuscript

The recorder comes back on.

FLEUR: Okay. Breakfast was eaten. It was very nice. So if I were to re-focus a bit on Yours the Face…

HANNAH: But I haven’t finished going on about things!

FLEUR: I’m sorry, I know. But that was purely to introduce you and what you do and what you think about. We’re meant to be talking about ma play!

So the other day we received a very positive review that very much overlooked the issue of consent within the play. It talked about the scene in which a girl was photographed naked, unconscious, drugged as ‘romantic’ and ‘touching’ and referred to her as ‘asleep’. Do you want to talk a bit about the historical context behind consent?

HANNAH: Yes, not just the question of consent but also the question of waiving consent: that it could appear romantic to that audience member that this should happen.

I been reading the Confessio Amantis by John Gower – well a tiny part of it because it is massive. This is a part where he retells a story from Ovid. It is the story of Philomela: her sister, Procne, marries this man, Tereus, and they go to live happily over in Thrace but she wants to see her sister so she sends her husband back to get her from her parents. Tereus falls in love with Philomela and rapes her and then, so that she can’t tell anyone, cuts out her tongue and locks her up in a prison.

The interesting thing to me is the framing of that story: obviously Gower thinks this is a horrible thing but the comments that the women make on it are “How could your betray your marriage vows to me like this?” and “How could you cheat on my sister?” Effectively, the problem is spouse breach. It is said in the framing narrative, “Don’t attempt to get love this way.” The implication seems to be that this is love. It is just the wrong way to go about it.

A caption beneath reading, ‘et tient le wodewose & rauist un des damoyseles coillaint des fleurs’, translation: ‘And the wodewose caught and ravist one of the damsels collecting the flowers.’ From the TAYMOUTH HOURS, England (London?), 2nd quarter of the 14th century.

There is a hunting metaphor running throughout the story. Tereus shows up in the form of various animals – he is a falcon, he is a wolf, he is a lion, he is a ravening beast – and she is the creature crushed in the falcon’s claw but… What was I talking about?

FLEUR: My play? Perhaps?

HANNAH: Yeah, your play. Yeah, the point is that this is framed as a hunting story and he is only wrong about this because he is not married to her and he is married to someone else so he can’t marry her. But it is still called love, framed as love. You have that idea that rape – sex – counts as love. It is something enacted by the man. She is saying ‘no’ – of course she is saying ‘no’, she should say ‘no’ – and you also have that image of the hunting metaphor running through a lot of romances of the Middle Ages and of much later as well. The point I’m getting to in a round about way – that you’ll probably have to edit substantially –

FLEUR: I really will.

HANNAH: – Is that there is this conceptual framework for romance as a hunt: for the woman to flee and the man to pursue and that’s the way the story is meant to go. That this is how heterosexual relationships work: if she wants to be caught, the woman has to flee. If she wants to marry him, if she wants to be a wife and not just somebody to be bedded and tossed aside, then she has to say ‘no’. She has to say ‘no’ repeatedly whenever she is asked until society (ie: her parents, her father, her brother, her male guardian) passes her on. I have seen the argument made that this is where we get our concept of modern romance.

FLEUR: That she keeps saying ‘no’ and he has to take this as a ‘yes’.

HANNAH: He has to assume that it is or can become a yes and that she must resist and he must pursue. That’s the premise, this argument goes, for the whole of Western, heterosexual romance since then.

We stop the recorder again. We go home. I tell Hannah that we have to actually talk about the play at some point. Bless.

FLEUR: Okay. So the play itself. Any thoughts on that?

HANNAH: Um… The word ‘romance’. You’ve been saying that some people have been watching this and seeing ‘yes, yes, yes’. It is struck me as I was watching it that part of the reason for that might be the word ‘Romance’, which comes from a particular kind of genre but also it is also certain a kind of expected narrative arch. It has always been the man acting and the woman being acted upon. Of course that changes a bit more recently. We do want to see the strong female character, although we do still have a fairly limited understanding of what that means but we still have the man initiating the action of the relationship and her receiving it. I think this makes a genre expectation – this expectation of how the story will play out in our minds – whenever we see this sort of thing.

It is very interesting when you put both those voices into one body. Part of the reason people might be seeing this story primarily from the masculine point of view is, well you obviously have a masculine body there, but in some wasy the male character’s voice is more persuasive more quickly in terms of getting you around to his point of view. Perhaps this might be different for a non-Australian audience, not because of the Australian accent but because of the Australian personality: more casual, more active, ‘come on in and share my story, be part of this story’.

But it’s not just that. It is a very gendered thing. Because he is very open and accessible and she is ‘standoffish’ in some ways. She is that glass face. We are focusing on her as a surface. We have words like ‘glass’ and ‘stone’ and ‘mummified’. Those images give a real focus to the surface and we are very aware that something lies below it but we don’t get invited into that. It takes a very long time to access her.

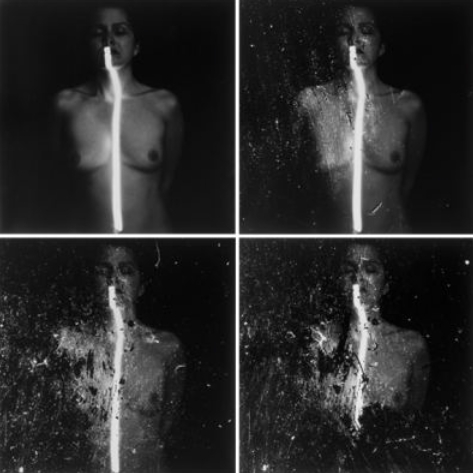

FLEUR: She is also very passive, as well. And that was a really deliberate choice on my part. I mean, there is ‘yes’ in this play, but it is not ‘enthusiastic consent’. It is “And I let him because he had a mouth and so did I” and okay fine, if you really want me to say that I want you, I’ll say that I want you. Also, he is very grossed out by her when she stops being passive. When she does reveal what’s underneath he wants to carry her away from his body.

But I think his accessibility is a really interesting thing, in terms of how people relate to him. He is a personable guy; we do want to like him –

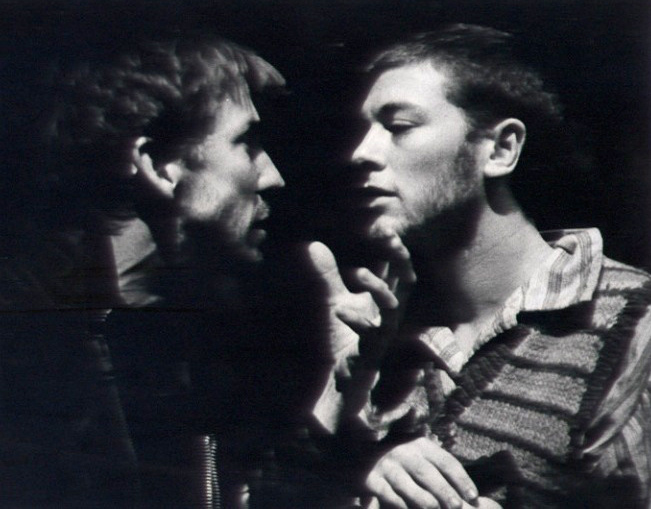

HANNAH: Even when he’s talking about “I could break her bones while she’s lying there”.

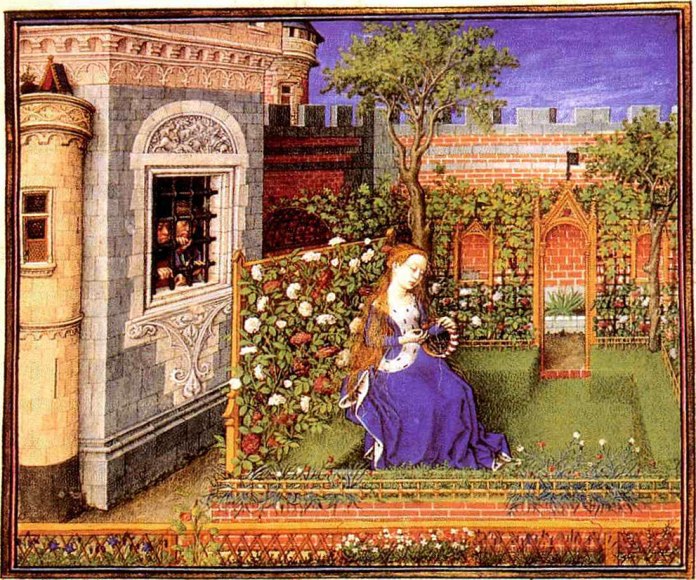

Roderick Cairns in YOURS THE FACE, photographed and designed by Sarah Walker

FLEUR: Yes! And some people can’t look past the casual, chatty tone. They can’t necessarily see that. And not many sexual assaults are this evil villain creeping around the streets at night being obviously the villain. It is usually someone who is known to the victim and it is often not brought to the police: not every case of a non-consensual action on another body is punished or even condemned. That’s what I wanted to show: she wakes up naked and they both know something is wrong but then these people then just go on with their lives. His actions are never questioned. And it is interesting how some people read that as being obviously incredibly fucked up and some people don’t because he was chatty, he was personable, we couldn’t see the almost lifeless body that he was standing over and no one wakes up and says, “You did a bad thing”.

HANNAH: Yes, and even in its darkest forms, the villain gets his comeuppance. We are very used to at least to some kind of acknowledgement within the story of “yeah okay, that was a bad action” and then there is a result. There is an acknowledgement within the text. And you are right: she is so passive that she isn’t the kind of person who I think would make that call, even on him let alone making it explicate to the audience.

And yes, her passivity does seem to make her fit perfectly into that ‘damsel’ role in some ways but also because she is on a pedestal, almost literally. She is the subject of the gaze. She is what everyone focuses on: the physical surface of her skin. I think even the first time that she spoke she said something like “the aim of every photo is to appear as if you are holding something back: that there is some kind of mystery” so –

FLEUR: “Make them think they haven’t got it all even if they have got it and you haven’t got a piece of your skin left to yourself and they’ll come back. They’ll want that last piece of you.”

HANNAH: Yes. That withheld ‘yes’ at the same time as they are in fact getting everything that she has, because at that point she thinks she is nothing but the surface as well.

“That last piece of you.” Peter Pan? The kiss at the corner of Mrs Darling’s mouth that Mr Darling could never get?

FLEUR: Oh yeah, yeah, yeah. A bit of Peter Pan always has to make its way into my writing. That was one of the subtler.

HANNAH: Was that deliberate?

FLEUR: No, but I love that you found some Peter Pan in it. Well shall we leave it there? That was beautiful. Thank you! We meandered to my play eventually!